Looking back on the legacy and influence of Snake Plissken.

Three words. Three small words introduced us to the baddest of all badasses, the man of few words, the one-eyed anti-hero Snake Plissken. My first introduction to the John Carpenter creation was on a television screen in Menorca at the age of 13. Escape From New York was playing on one of the channels in Spanish without any subtitles, making it difficult to understand. What caught and kept my attention was the incredible opening theme music, as well as the gritty and slightly futuristic look. I couldn’t look away.

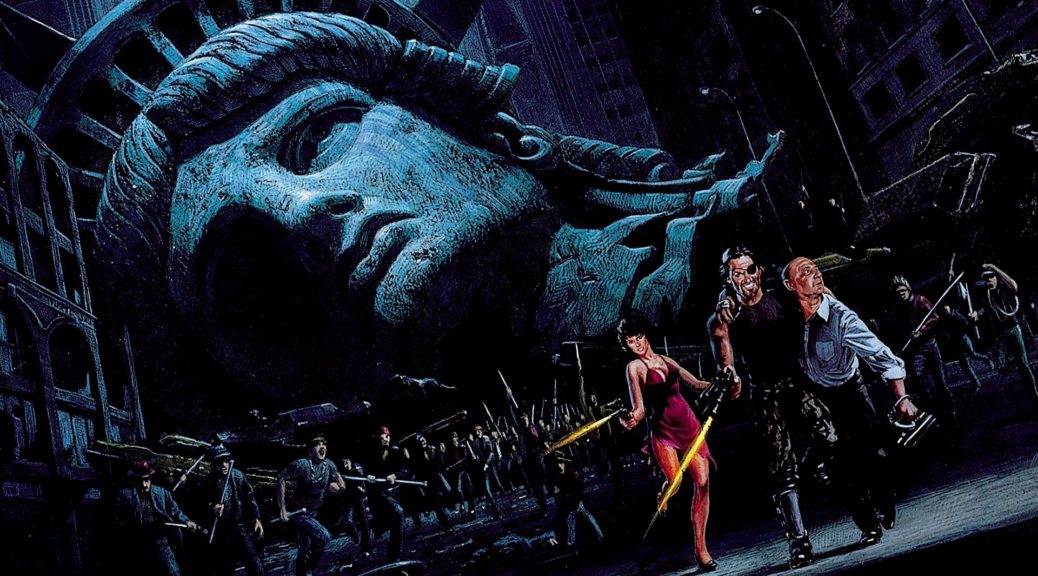

When we were back in England I asked my parents to get me a copy of the film on VHS. Months later it was my 14th birthday and inside the colourful wrapping paper was a black VHS case with an image that remains iconic in my mind to this day: the giant decapitated head of the Statue of Liberty on the ground and three people being chased by a hoard of men with “John Carpenter’s Escape From New York” plastered on the cover. I jumped for joy and broke open the case immediately and removed the cellophane that covered the tape. I slid the cassette into my video player and I pressed play.

For the next 90 minutes I was transported to the grimy streets of Manhattan Island Maximum Security Penitentiary in the futuristic world of 1997 (bear in mind I saw this in 2001) and introduced to a cast of characters that were quirky, chilling, cool, dangerous and fun. I was totally immersed in the film and when it was over I rewound the tape to the beginning and watched it again. The high-tech police force contrasted against the no-tech prison fascinated me, but the biggest draw for the whole film for me was Plissken himself.

The character of Snake Plissken had gone on to inspire the character of Solid Snake in Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid series, and only upon replaying it did I realize the connection. Let’s face it, Solid Snake is Snake Plisken and the game was basically Escape From New York: The Game. His gruff, gravelly voice is practically an imitation of Plissken’s. Both are forced into taking their assignments, both are captured, both find a tough female and neurotic male ally on the inside, and their only communication with the outside world is through a radio. As if that weren’t enough, both Solid Snake and Snake Plissken sport the iconic eye patch.

But I digress. Escape From New York was not some big-budget blockbuster, instead it was shot on a relatively low budget in St Louis. In fact, there is only one “New York Shot” and even that was actually two different shots edited seamlessly together. This is because they could only afford to shoot for one day in New York.

The shot in question is the tracking shot where Rehme walks into the Liberty Island Security Control room to get the call from air traffic control. The shot pans over into complete blackness, and then with a cut we find ourselves in Los Angeles as the panning shot continues on, showing the helicopters and approaching prisoner transfer bus. It’s a seamless edit that I wouldn’t have even known existed until I watched a documentary about the making of the film.

Throughout Escape, Snake acts as an of angel of death of sorts. Everyone he interacts with inside of the walls of the prison ends up dead, with exception of the President. He’s also pursued by death by way of the countdown on his watch, which promises his own demise. Because of this he has a do-anything attitude to accomplishing his mission, ready to screw anyone over who can help him find the President.

Kurt Russell talks in an interview about the moment he knew that the character of Snake was going to be a hit, they were shooting one night and John Carpenter wanted a shot of him running down the street and turning down an alley. They shot it and as Kurt turned the corner there were four big guys coming around the corner from their side. Because of the eye patch he wore Kurt had gotten into the habit of tilting his head to look at people and as he did that the four big guys backed away saying “Easy, easy, it’s cool.” After coming back out of the alley and back down to where the crew were set up Kurt said to John Carpenter, “I think this character’s gonna work.”

And of course it works. Snake Plissken just oozes a pure sense of “Do not fuck with me” in every scene in the film. He has such a presence on screen. It’s clear to see how Kurt Russell became the huge movie star that he is today off the back of his performance in Escape From New York.

The opening title sequence does an incredible job of setting up the world through voice over, provided by an un-credited Jamie Lee Curtis, and enhanced by Computer Generated Imagery. It is not the only piece of fake CGI that is in the film, for the sequence were Snake enters the prison he is flying a glider that has computer generated images of the cityscape, or so we the audience are led to believe. In actuality the CGI we are looking at is actually a scale model of the city with the corners of the buildings covered in high contrast tape and filmed it under a black light. The realistic models of New York were achieved by laying out a map of the city and scale model buildings made from cardboard and plywood were placed on top, the streets were blacked over with tape to give them a realistic look of a street. For the POV shot of the plane speeding towards New York the effects team painted the studio floor with a high gloss black paint to simulate the water that surrounded Manhattan Island. Future director James Cameron worked on the film, providing some of the matte paintings and working on the effects shots of Air Force One.

The supporting cast are fantastic in their respective roles. Lee Van Cleef plays the role of Hauk – the opposite of Snake. It’s easy to see that if Snake had remained on the side of the law he could have ended up just like Hauk. Hauk is just as fearless as Snake, and their first meeting shows how tough he is when four guards have brought Snake to him and he asks them to leave them alone. Throughout the film he is the only one who really believes that Snake can accomplish his mission, even though he can be seen as an antagonist for Snake he is also his only ally on the outside. This is a recurring theme in the film: snake’s allies are also his enemies. Brain – played by Harry Dean Stanton – double-crosses him multiple times.

The characters are quite well-developed for what is really a B-movie; they all have their own backstories. Donald Pleasence came up with an entire backstory for why the President of the United States is British. None of it was used but it was that sort of work that informed his performance creating a solid character. He also brought some of his own real-life experiences of being a Prisoner of War in his performance, the blonde wig he is wearing when Brain and Maggie break him out was his idea.

Issac Hayes portrayed the Duke of New York with an imposing level of seriousness. When he spoke he spoke with a slow and deliberate manner to make people listen and pay attention to every word he said. There was also some very subtle things that Hayes injected into the role. The Duke has a slight twitch in his right eye which is only seen a few times but it adds a level of depth to the character that not many other B movies would have in their characters. In contrast to the serious Duke of New York there is his right hand man Romero, named after director George A. Romero. Everything about Romero was to the extreme from his general look to his over the top performance, he is the audience’s first glimpse of the occupants of New York and it leaves an impression. His creepy demeanor as he slowly counts down from twenty still makes an impact today. Romero was portrayed by Frank Doubleday who appeared in Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 as the robotic and unfeeling White Warlord who calmly guns down a 12 year old girl. Here he is the opposite, everything is over the top in his performance. Doubleday was given total creative freedom when it came to Romero, the voice and look were all his choices.

Where the story is quite a simple one, what really makes it work is Carpenter’s direction and world building. The creepiness and desolation of New York makes it a character in itself. Carpenter originally wrote the screenplay in 1974 as a response to the Watergate scandal, it was turned down by various studios for amongst other reasons they felt it was too violent. He put it to one side until the success of Halloween allowed him to strike a two-picture deal with Avco Embassy, the other film being The Fog. Carpenter brought in his friend Nick Castle to polish up the script. Castle had played The Shape in Carpenter’s Halloween years earlier. Some of Castle’s changes were to add a sense of humour to the film. He also tweaked the ending that Carpenter felt needed some work.

Where Halloween is probably seen to be John Carpenter’s most successful film, Escape From New York is easily his most ambitious. I recently saw the film in a packed cinema and was once again glued to the screen throughout. The moment Carpenter’s score kicked in a smile came across my face and I was engrossed from start to finish. It’s nice to see that all these years later the film can still keep me engrossed the same as it did all those years ago. If I had the option, I would have tried to get the cinema to restart the movie from the beginning. It’s easy to see why the film and the character of Snake Plissken has become such a cinematic icon, even though the attempt to continue the story of Snake Plissken did not live up to the original’s gritty and grimy tone it didn’t stop the character from being any less iconic.

The only way I can think to wrap this up is by quoting the man himself, “The name’s Plissken!”

Matt is a huge film and TV buff who studied film and moving image production at university. In his spare time he enjoys reading comics and books, the occasional gaming session and writing novels.