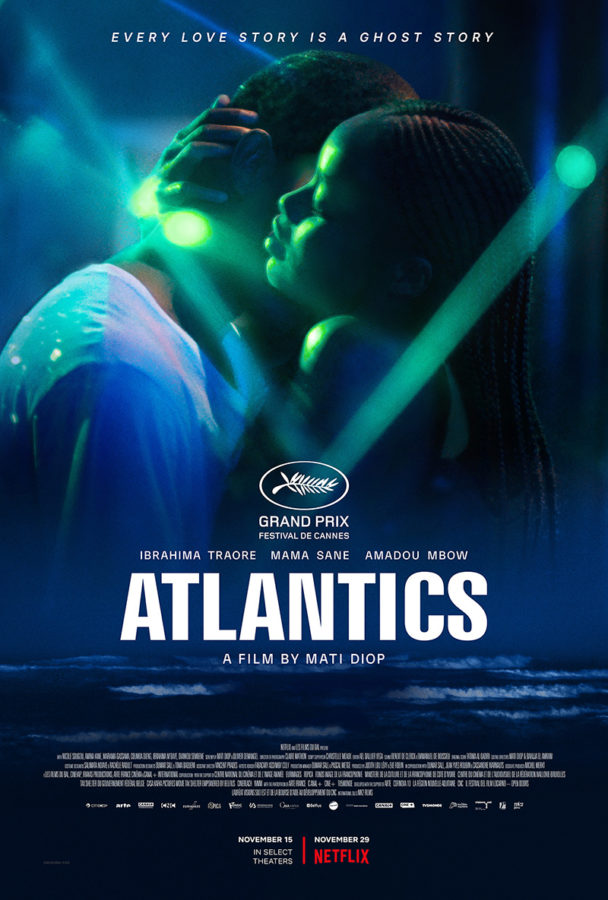

Hey! It’s been a long winter vacation, but I’m back this week with French director Mati Diop’s supernatural indie drama ATLANTICS, now available on Netflix.

On New Year’s Day, for some reason, my partner put TRANSFORMERS: DARK OF THE MOON on the TV first thing in the morning. That night, we decided to watch 6 UNDERGROUND, completely not intending to make it a full circle Michel Bay kind of day. And if there’s one thing I learned from that experience, it’s that if you’ve ever wondered what the opposite of a Michael Bay movie is, it’s ATLANTICS.

ATLANTICS tells the story of a young Senegalese woman, Ada, who despite being engaged to a rich asshole, is in love with a construction worker named Souleiman, who, along with his coworkers, is not paid his promised salary for 4 months of work on a huge tower that looms over the town of Dakar. In order to find work, the men all hop on a boat and try to cross the sea to Spain, leaving their women behind. The men don’t reach their destination, and that’s when weird shit starts happening.

SPOILERS AHEAD

The supernatural stuff doesn’t even start until halfway through the film, when the souls of the men, who never made their destination, enter the bodies of the women they left behind and demand their money from the rich boss at the construction site.

So how is this the opposite of a Michael Bay movie (And I say this as someone who loves many of Michael Bay’s explosion-fests)?

- It’s not about white people.

- It’s lit with either natural light or very low light that is as practical as possible.

- There are long takes of people just walking, or ocean waves crashing.

- Sometimes a conversation is shot almost entirely from one side with no cuts.

- I didn’t feel tired when it was over.

- The fire was done entirely with lights or stock footage, so there were no actual explosions.

How is it like a Michael Bay movie? Lots of handheld shots.

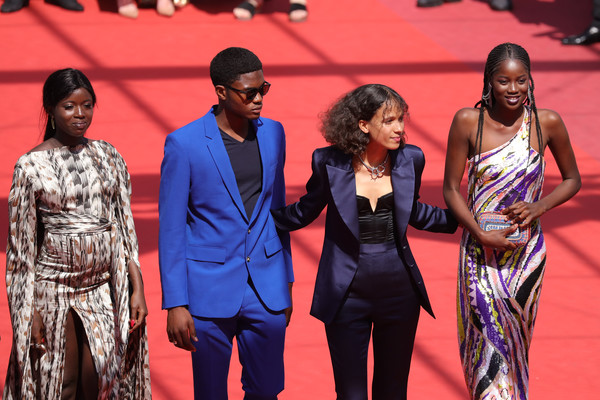

Diop’s family is from Senegal, and it’s clear that she wanted to showcase the culture and the land. There are long takes of the beach. Ada’s wedding is more about the people around her, expressing joy on what they feel is a joyous occasion. Ada’s girlfriends feel like real people with individual personalities and desires, and not just sidekicks. There is a deft hand at play here- using subtlety to ask questions about slut shaming and the wide gap between right and poor that forces these men to risk their lives in search of a better life. Nobody makes any big speeches about meaning – they just tell their story and let us learn from it what we will.

The film debuted at Cannes to great critical acclaim, almost craving the top prize. Critics have universally lauded it, and it is indeed a beautifully shot, very patient film.

However, I didn’t find a whole lot of articles talking about the thing that really bothered me.

This film had a female writer/director, but it also had a heavy female presence on its crew. There seems to have been a conscious effort made to make sure women were heavily involved in making this story, and the image of a group of women mindlessly marching into a rich man’s house and scaring the shit out of him because they look like possessed spirits is indeed a powerful one – but something just kept nagging at me as I watched it.

The men possess these women against their will. They get sick, and marching around at night barefoot makes their feet bloody. They have no recollection of what they’ve done. It is, quite frankly, a violation. They don’t talk about it – it’s barely mentioned – so although this film is subtle, I don’t think we’re supposed to be thinking about the violation. The story is about men taking over women, and even though we’re looking at women, the story is not theirs. The whole story is entirely about what the men have gone through – except for Ada.

Which brings me to Ada’s story. There is a police officer who was investigating an arson related to Ada’s fiancé. Souleiman possesses him and uses his body to have sex with Ada, the woman he love and left behind. That’s rape, everybody. This man’s body was used so a ghost could have sex with his girlfriend. It’s set up as a moment of love – just as this has been called a love story by most critics – but it’s also a story about a man who was victimized by a ghost. This is a very subtle film and it asks questions more than it answers them, and maybe we’re meant to understand that this is a horrific moment for him, but it doesn’t seem so. He looks unhappy, but he says nothing, and in the end, the fallout is simply him closing the case. There’s never a signal that any of this body possession is selfish and a violation. It’s presented more as a gift to the dead men as a way to help them find peace. The women certainly are paid for it, but they never got a chance to choose, just as the police officer never got a chance to choose to have sex with Ada.

As I mentioned, this film is subtle, so maybe we were supposed to draw our own conclusions. If so, I’m not sure the work was done to get us there.

If you’ve read this far, I’ve already spoiled the film for you, but I’m curious if anyone else had the same uncomfortable reaction I did, so I encourage you to make your own conclusions and check it out Netflix if you haven’t already, especially if you’re in the mood the anti-Michael Bay.

Let me know what you think! Hit me up on Twitter – @TheEmilyBlake – or comment below.

I’m resuming regular weekly articles (I hope) and next week will be BOOKSMART, directed by Olivia Wilde.

Emily Blake writes screenplays with lots of fight scenes. She is a vocal advocate for feminism, polyamory, kink, and sex positivity. She makes most of her money as a script supervisor for film and television, but she also makes cosplays for clients out of her little apartment in Los Angeles.